Theodore (602 – 19 September 690; sometimes known as Theodore of Tarsus or Theodore of Canterbury[1]) was the eighth Archbishop of Canterbury, best known for his reform of the English Church and establishment of a school in Canterbury.

Theodore's life can be divided into the time before his arrival in Britain as Archbishop of Canterbury, and his archiepiscopate. Until recently, scholarship on Theodore had focused on only the latter period since it is attested in Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English, and also in Stephen of Ripon's Vita Sancti Wilfrithi, whereas no source directly mentions Theodore's earlier activities. However, Michael Lapidge and Bernard Bischoff have reconstructed his earlier life based on a study of texts produced by his Canterbury School.

Early life

Theodore was of Byzantine Greek descent born in Tarsus in Cilicia, a Greek-speaking diocese of the Byzantine Empire.[2] Theodore's childhood experienced devastating wars between Byzantium and the Sassanid Empire, which resulted in the capture of Antioch, Damascus, and Jerusalem in 613-614. Tarsus was captured by Persian forces when Theodore was 11 or 12 years old. There is evidence that Theodore had experience of Persian culture.[3] It is most likely that he studied at Antioch, the historic home of a distinctive school of exegesis, of which he was a proponent.[4] Theodore also was familiar with Syrian culture, language and literature, and may even have traveled to Edessa.[5]

Though it was possible for a Greek to live under Persian rule, the Arab conquests, including Tarsus in 637, certainly drove Theodore from Tarsus; if he had not fled earlier, Theodore would have been 35 years old when he left his birthplace.[6] Following this, he studied in the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, including the subjects of astronomy, ecclesiastical computus, astrology, medicine, Roman civil law, Greek rhetoric and philosophy, and the use of the horoscope.[7]

At some time before the 660s, Theodore had come west to Rome and was living with a community of Eastern monks, probably at the monastery of St. Anastasius.[8] At this time, in addition to his already profound Greek intellectual inheritance, he became learned in Latin literature, both sacred and secular.[9] The Synod of Whitby (664), having confirmed the decision in the Anglo-Saxon Church to follow Rome, in 667, when Theodore was 66, the see of Canterbury fell vacant. Wighard, the man chosen to fill the post unexpectedly died. Wighard had been sent to Pope Vitalian by Ecgberht, king of Kent, and Oswy, king of Northumbria, for consecration as archbishop. Following Wighard's death, Theodore was chosen upon the recommendation of Hadrian (later abbot of St. Peter's, Canterbury). Theodore was consecrated archbishop of Canterbury in Rome on 26 March 668, and sent to England with Hadrian, arriving on 27 May 669.

Archbishop of Canterbury

Theodore conducted a survey of the English church, appointed various bishops to sees that had been vacant for some time,[10] and then called the Synod of Hertford to institute reforms concerning the proper celebration of Easter, episcopal authority, itinerant monks, the regular convening of subsequent synods, marriage and prohibitions of consanguinity, and others.[11] He also proposed dividing the large diocese of Northumbria into smaller sections, a policy which brought him into conflict with Bishop Wilfrid, whom Theodore himself had appointed to the See of York. Theodore deposed and expelled Wilfrid in 678, dividing his dioceses in the aftermath. The conflict with Wilfrid was not finally settled until 686–687.In 679, Aelfwine, the brother of King Ecgfrith of Northumbria, was killed in battle against the Mercians. Theodore's intervention prevented the escalation of the war and resulted in peace between the two kingdoms, with King Æthelred of Mercia paying weregild compensation for Aelfwine's death.[12]

Canterbury School

Theodore and Hadrian established a school in Canterbury resulting in a "golden age" of Anglo-Saxon scholarship:[13]- They attracted a large number of students, into whose minds they poured the waters of wholesome knowledge day by day. In addition to instructing them in the Holy Scriptures, they also taught their pupils poetry, astronomy, and the calculation of the church calendar...Never had there been such happy times as these since the English settled Britain.

Pupils from the school at Canterbury were sent out as Benedictine abbots in southern England, disseminating the curriculum of Theodore.[18]

Theodore called other synods, in September 680 at Hatfield, Hertfordshire, confirming English orthodoxy in the Monothelite controversy,[19] and circa 684 at Twyford, near Alnwick in Northumbria. Lastly, a penitential composed under his direction is still extant.

Theodore died in 690 at the remarkable age of 88, having held the archbishopric for twenty-two years, and was buried in Canterbury at Saint Peter's church.

Veneration

Theodore is venerated as a saint on September 19 in the Church of England, Episcopal Church (USA), and Eastern Orthodox churches. He is also recorded on this day in the Roman Martyrology. Canterbury also recognizes a feast of his ordination on 26 March.[1]Footnotes

- ^ a b c Farmer 2004, pp. 496–497.

- ^ Bunson 2004, p. 881; Bowle 1979, p. 160; Bowle 1971, p. 41; Ramsey 1962, p. 2; Johnson & Zabel 1959, p. 403.

- ^ Lapidge 1995, Chapter 1: "The Career of Archbishop Theodore", pp. 8–9.

- ^ Lapidge 1995, Chapter 1: "The Career of Archbishop Theodore", p. 4.

- ^ Lapidge 1995, Chapter 1: "The Career of Archbishop Theodore", pp. 7–8.

- ^ Lapidge 1995, Chapter 1: "The Career of Archbishop Theodore", p. 10.

- ^ Lapidge 1995, Chapter 1: "The Career of Archbishop Theodore", pp. 17-18.

- ^ Lapidge 1995, Chapter 1: "The Career of Archbishop Theodore", pp. 21–22.

- ^ Bede & Plummer 1896, 4.1.

- ^ Bede & Plummer 1896, 4.2 (Appointments: Bisi to East Anglia, Aelfric Putta to Rochester, Hlothhere to Wessex, and Ceadda after reconsecration to Mercia).

- ^ Bede & Plummer 1896, 4.5 (Canons of Hertford).

- ^ Bede & Plummer 1896, 4.21.

- ^ a b Bede & Plummer 1896, 4.2.

- ^ Bischoff & Lapidge 1994, p. 172.

- ^ Bischoff & Lapidge 1994.

- ^ Stevenson 1995.

- ^ Siemens 2007, pp. 18–28.

- ^ Cantor 1993, p. 164.

- ^ Collier & Barham 1840, p. 250.

References

- Bede; Plummer, Charles (1896). Historiam ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum: Historiam abbatum; Epistolam ad Ecgberctum; una cum Historia abbatum auctore anonymo. Oxford, United Kingdom: e Typographeo Clarendoniano. doi:731. http://books.google.com/books?id=y5mAkgAACAAJ.

- Bischoff, Bernhard; Lapidge (1994). Biblical Commentaries from the Canterbury School of Theodore and Hadrian. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521330890. http://books.google.com/books?id=MI6bpmlzOs0C.

- Bowle, John (1979). A History of Europe: A Cultural and Political Survey. London, United Kingdom: Secker and Warburg. http://books.google.com/books?id=HfsTAQAAMAAJ.

- Bowle, John (1971). The English Experience: A Survey of English History from Early to Modern Times. London, United Kingdom: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. http://books.google.com/books?id=i8MIAQAAMAAJ.

- Bunson, Matthew (2004). OSV's Encyclopedia of Catholic History. Huntington, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitor Publishing. ISBN 1592760260. http://books.google.com/books?id=dWpO1--eMrYC.

- Cantor, Norman F. (1993). The Civilization of the Middle Ages: A Completely Revised and Expanded Edition of Medieval History, the Life and Death of a Civilization. New York, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Incorporated. ISBN 0060170336. http://books.google.com/books?id=5tQYAAAAYAAJ.

- Collier, Jeremy; Barham, Francis Foster (1840). An Ecclesiastical History of Great Britain (Volume 1). London, United Kingdom: William Straker. http://books.google.com/books?id=1o03AAAAMAAJ.

- Earle, J. J.; Plummer, Charles (1899). Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Oxford, United Kingdom.

- Farmer, David Hugh (2004). Oxford Dictionary of Saints (Fifth ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198609490. http://books.google.com/books?id=qx4VQwAACAAJ.

- Haddan, Arthur West; Stubbs, William; Wilkins, David (1869). Councils and Ecclesiastical Documents Relating to Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 1. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press. http://books.google.com/books?id=7yARAAAAYAAJ.

- Johnson, Edgar Nathaniel; Zabel, Orville J. (1959). An Introduction to the History of Western Tradition, Volume 1. Ginn. http://books.google.com/books?id=WcsYAAAAYAAJ.

- Lapidge, Michael (1995). Archbishop Theodore: Commemorative Studies on his Life and Influence. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521480779. http://books.google.com/books?id=GW216kEO6EgC.

- Ramsey, Michael (1962). Constantinople and Canterbury: A Lecture in the University of Athens: 7 May 1962. S.P.C.K.. http://books.google.com/books?id=eJtIAAAAMAAJ.

- Raine, Eddius (1879). "Vita Wilfridi Episcopi auctore Eddio Stephano". The Historians of the Church of York and its Archbishops, Issue 71, Volume 1. London, United Kingdom: Longman & Co. http://books.google.com/books?id=2lXSAAAAMAAJ.

- Siemens, James R. (2007). "Christ's Restoration of Humankind in the Laterculus Malalianus, 14". The Heythrop Journal 48 (1): 18–28. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2265.2007.00303.x.

- Stevenson, Jane (1995). The 'Laterculus Malalianus' and the School of Archbishop Theodore. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521374618. http://books.google.com/books?id=TxJkw-nfy88C.

St. Theodore of Tarsus and Canterbury is the patron saint of the Antiochian Orthodox Church in the United Kingdom and Ireland; that is of the Deanery and the Cathedral parish of St. George in London. As a "son of Antioch" coming from Tarsus, the saint is notable for putting the organisation and life of the Church in these isles on a proper footing in the 7th Century. His contribution and legacy has been immense. He remains an inspirational figure for the Church's mission today.

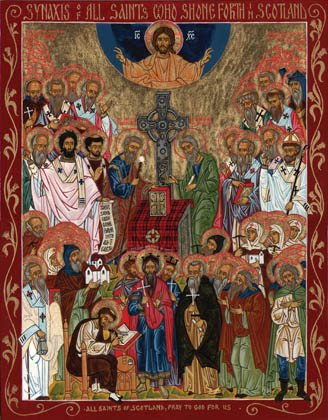

This Icon (above) from Aidan Hart Icons

No comments:

Post a Comment